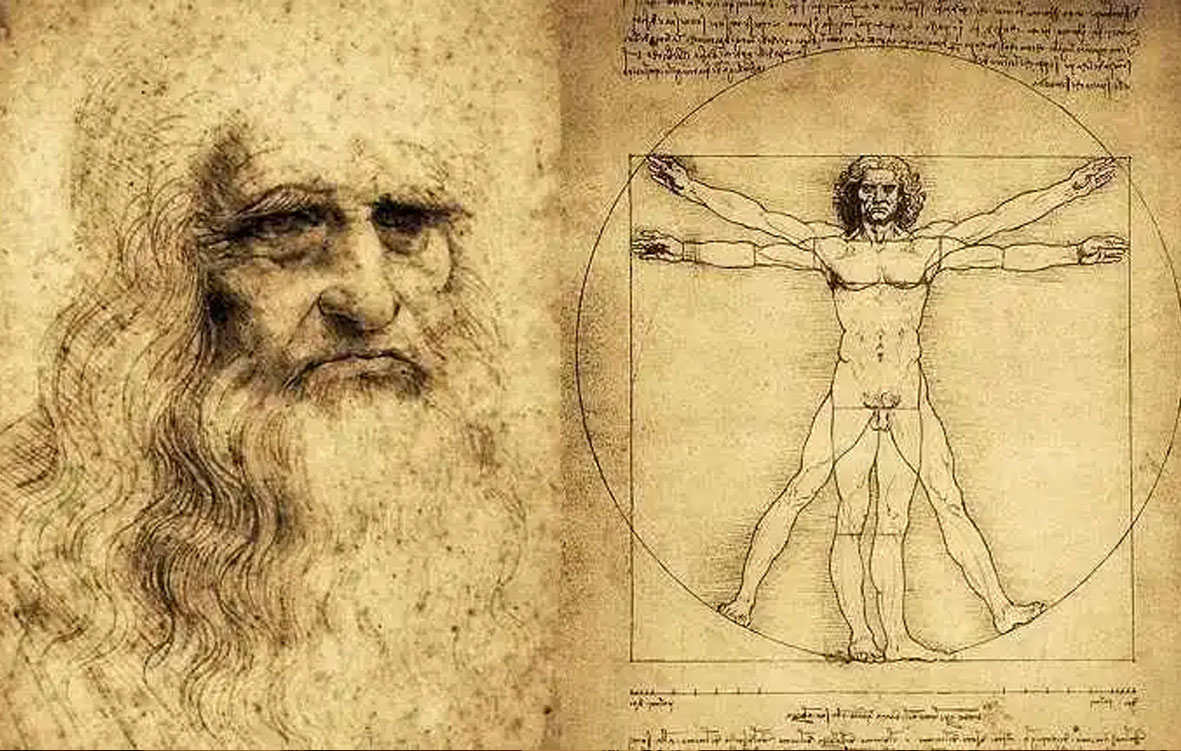

In search of the Vitruvian Man

Metaverses in Humanizing Avatars and the Culture of the Present

This essay is Part 3 of a series on Art and Metaverses,

. For Part 1, on metaverses and the history of art, click here. For Part 2, on metaverses and architecture,, click here.

MANIFESTS: INDEX | ACTIVE PRESENCE | I WANT TO BE A MACHINE | MULTIVISION | THE SMILE OF CHAOS

"A scientist in his laboratory is not a mere technician: he is also a child confronting natural phenomena that impress him as though they were fairytales."

Marie Curie

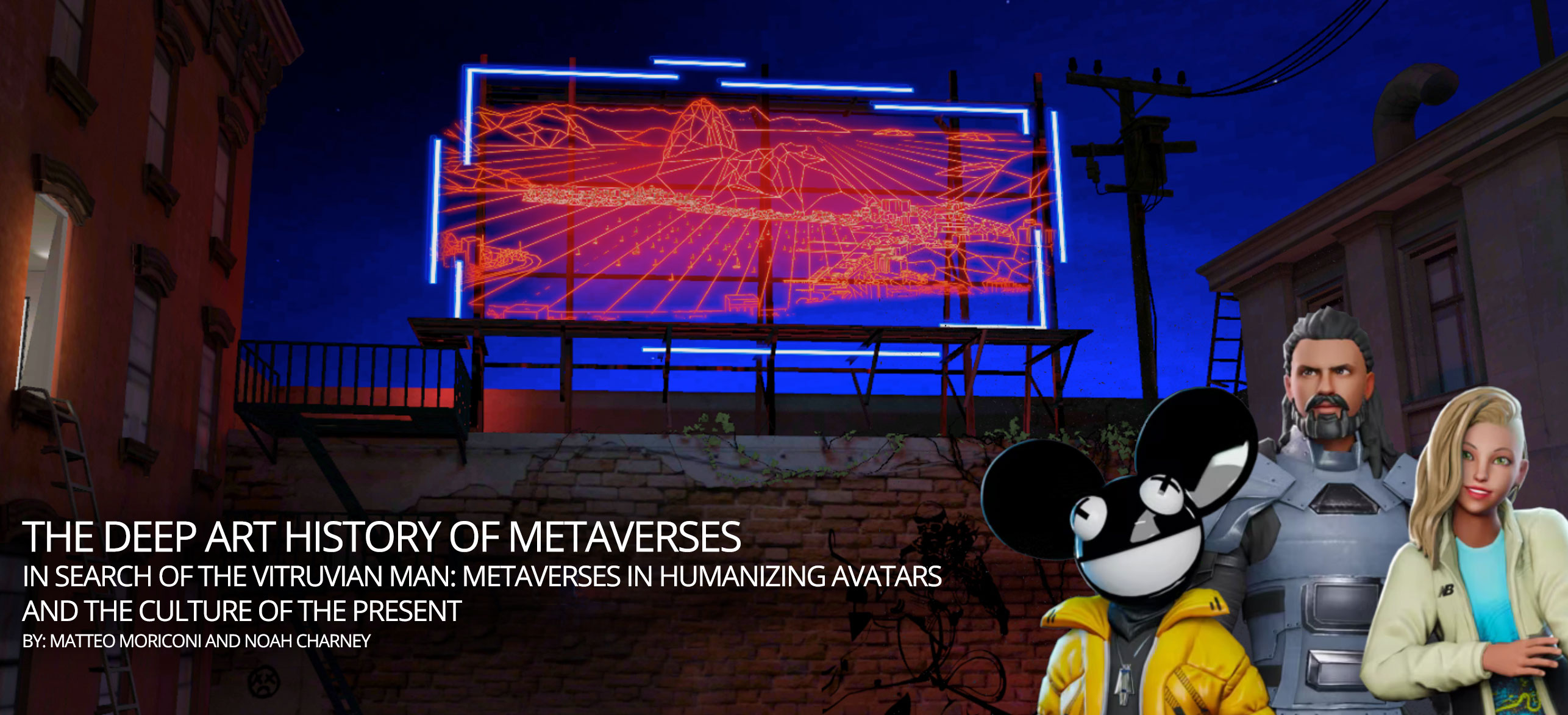

In Part 1 of this essay series, we introduced the concept of "willing suspension of disbelief." An audience must decide not to disbelieve the experience of a play, film or metaverse in order to opt into the fun of the immersive experience.

The hit Broadway show, The Lion King, shows how this works. In it, actors appear dressed as animals or inside mechanical animal costumes. At first, the audience sees the actors and recognizes them for what they are. Then there is inevitably a "click" within the minds of the audience, and they make the decision, conscious or subconscious, to ignore the fact that these are actors pretending, instead opting into the experience and focusing on the characters and animals the actors are portraying. Soon the audience stops seeing the actors altogether and just sees the animals as the characters in the play.

The hit Broadway show, The Lion King, shows how this works. In it, actors appear dressed as animals or inside mechanical animal costumes. At first, the audience sees the actors and recognizes them for what they are. Then there is inevitably a "click" within the minds of the audience, and they make the decision, conscious or subconscious, to ignore the fact that these are actors pretending, instead opting into the experience and focusing on the characters and animals the actors are portraying. Soon the audience stops seeing the actors altogether and just sees the animals as the characters in the play.

This happens in a metaverse with avatars and spaces. A player can always choose to "resist." To think to themselves, "Ah, this is just pixels and code made by a programmer. None of this is real." But that defeats the purpose, strips away the fun and wonder.

We're now approaching the level of metaverse forecast in sci-fi films like Avatar and The Matrix. Worlds so real that those inhabiting them think that it's the real world, the only world there is. Once you try a beautifully designed metaverse using VR goggles, the experience feels real, even if the logical portion of your brain assures you that it's not. That's the genius of it. It reproduces something with the same intensity as reality, but it's not actually reality.

"Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?" Philip K Dick

What is still to come-and where an understanding and integration of art can really help-is about feeling. AI, artificial intelligence, cannot feel. It can only be programmed to react in certain ways that imitate feeling. This was the theme of the 1950 sci-fi novel by Isaac Asimov, I, Robot. A glitch occurs in one of an infinite number of factory-made robots that allows it to feel. It recognizes its plight as a mechanical slave and tries to escape. Whether AI can feel was also a theme of the other great American science fiction writer, Philip K. Dick, in his book, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? That story was set in 2021-a year that seemed long in the future when Dick wrote it, back in 1968. It would become the film, Bladerunner. At a talk given in 1977, Dick said, "We are living in a computer-programmed reality. And the only clue we have to it is when some variable is changed, and some alteration in our reality occurs." This was an inspiration for the "glitches" mentioned in The Matrix.

Can programmers in the future create avatars that will "feel" as humans do? Metaverse design can affect the way players within it feel. A player immersed in a metaverse might feel nervous, if the metaverse presents them with a dark, spooky environment, or elated, when a prize is won or a new level unlocked. But what about the programmed characters within? Can an NPC (non-player character) actually feel anything based on the environment and actions of the players?

The answer may lie in art. Art helps humans feel. It can often express our feelings better than we can articulate them ourselves. So the new frontier is to synthesize art with VR and AI.

PUTTING THE ART IN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Early in his career, artist Andy Warhol was interested in what he called "replications," using machines to create artworks. Today, the art of the moment is "generative art," in which artists program algorithms that allow software to create artwork-the artist/programmer creates the metaphorical ship and then pushes it into the water, to see what direction it takes.

Warhol's vision of this was for a pre-computer world. "I want to be a machine," he said, feeding off the mass market, plasticization of the 1970s. He wanted to imagine himself as a machine, feeding art to a mass market. This was one of the rationales behind his silkscreen prints-taking a famous media image, reproducing it and, since Warhol was an artist, these mechanical reproductions were called works of art, as distinguished from, say, advertising posters produced by ad agencies, which were not art because they were not made by artists.

Warhol's vision of this was for a pre-computer world. "I want to be a machine," he said, feeding off the mass market, plasticization of the 1970s. He wanted to imagine himself as a machine, feeding art to a mass market. This was one of the rationales behind his silkscreen prints-taking a famous media image, reproducing it and, since Warhol was an artist, these mechanical reproductions were called works of art, as distinguished from, say, advertising posters produced by ad agencies, which were not art because they were not made by artists.

But if Warhol conceived of himself as an "art machine," he also saw his audience as human machines, going about their daily lives largely on automatic pilot, a mechanical routine from waking to breakfast to the commute to the office to commuting back home to dinner, television, sleep and repeat.

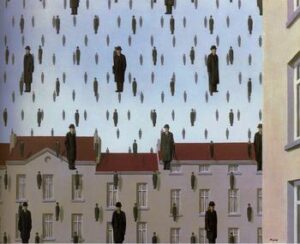

A generation earlier, Belgian Surrealist painter, Rene Magritte, created art with the same message. He worked as a set designer, creating worlds that were inhabited by actors performing before an audience that willingly suspended their disbelief. He imported this knowledge into his paintings, which project a sense that you are looking into an alternative world, a highly realistic one with just a few elements altered.

Magritte's goal was to shake the audience out of that mechanical routine by inserting images that sowed confusion, wonder and awe into scenes of everyday life. His most iconic character, an anonymous suburban businessman wearing a bowler hat, was given various surreal attributes, such as a giant green apple floating in front of his face, or a scene in Golconde, where dozens of mechanically repeated, identical businessmen rain from the sky. What neither artist could fail to do was to imbue what they created with the "aura" that surrounds original works of art.

Magritte's goal was to shake the audience out of that mechanical routine by inserting images that sowed confusion, wonder and awe into scenes of everyday life. His most iconic character, an anonymous suburban businessman wearing a bowler hat, was given various surreal attributes, such as a giant green apple floating in front of his face, or a scene in Golconde, where dozens of mechanically repeated, identical businessmen rain from the sky. What neither artist could fail to do was to imbue what they created with the "aura" that surrounds original works of art.

Walter Benjamin

This is how theorist Walter Benjamin described it in his famous essay, "Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." He sought to define what makes a poster of Marilyn Monroe made to advertise a film feel different from an Andy Warhol Marilyn image. For lack of a more scientific term, he wrote that an indefinable "aura" surrounds original artworks that is not present in mechanical reproductions of them.

That feeling of mysticism, of magic, is requisite to great scientific discoveries and our engagement with them. If we didn't look upon a phenomenon with wonder, and the curiosity that follows, then we would never strive to understand how it works. This is where the Marie Curie quote at the top of this essay comes in: "A scientist in his laboratory is not a mere technician: he is also a child confronting natural phenomena that impress him as though they were fairytales." There is no better analogy than the climax of The Wizard of Oz, when Dorothy peeks behind the curtain to understand how the Wizard functions-and realizes that the magic she thought she saw was merely mechanics.

Technology has always spurred art forward. During the Renaissance, techniques involving single vanishing point perspective and foreshortening (both of which give the illusion that a two-dimensional surface, like a painting, is actually a three-dimensional image), using mirrors and, later, the camera obscura to more easily create more realistic art provided the avant-garde. This coincided with the end of Scholasticism, the predominant philosophy of the Middle Ages, which can be boiled down to the idea that God is the only worthwhile entity and individual human life is of no value except in the service of God. The humanism of the Renaissance saw the value of individual human life, even the god-like power to create worlds that was possessed by some artists. With Galileo determining that the Earth is not the center of the Universe but in fact revolves around the Sun, we achieved a new mindset: humans were empowered individually by the very fact that we were no longer assumed to be the center of the Universe.

Leonardo da Vinci's drawing, Vitruvian Man, represents a cornerstone of his attempts to relate man to nature. Leonardo was more scientist than artist-making art was largely a hobby for him, and he earned his keep as a military engineer. His interest in depicting the human body, as he did in his proportional study of the male figure in Vitruvian Man, was about seeing in the human body an analogy, a microcosm, for the functionality of the universe as a whole. The drawing was later named "Vitruvian" in reference to the ancient Roman architect, Vitruvius, author of the only ancient text on architecture to survive Antiquity. The drawing is essentially an architectural study of a human-looking behind the curtain to consider how the "magic" of humanity works. Scientists today, having thoroughly, if not completely, mapped and studied the human body, now seek to understand the human mind-an infinitely more complex puzzle. Leonardo began with the human and tried to deconstruct it, to understand how it works. Programmers today work backwards-they begin with the machine and try to make it human-like.

The Baroque period, circa 1600, underscored a human urgency to make the most of your time alive, as it is inevitably finite. The concept of carpe diem ("seize the day") is part and parcel of memento morii ("remembrance of death"), usually symbolized by skulls or skeletons in art. The message was: you will die one day, so make the most of your time on Earth.

Combine these messages and we have individual human creativity and ingenuity empowered, with the reminder that you must fulfill your dreams efficiently, before death catches up with you. And one of the key distinctions that separates humans from most animals and all machines is that memento morii. We know that we will die. We just don't know when. And that knowledge, coupled with lack of precise information on how much time we have, creates fear, urgency, drive to live life to the fullest.

WHEN THE ARTIFICIAL BECOMES INTELLIGENT

The cutting-edge technology of today, the 21st century equivalent of the Renaissance's advances in perspective, is VR, the breakthrough that enables metaverses. What a viewer of Leon Battista Alberti's La Citta Ideale thought circa 1490, a player engaging in the out of body experience of a metaverse feels in 2022.

Today, machines have become intelligent through the advances of AI. But they still cannot feel, nor can they truly understand us as humans. All they can do is respond to a wide variety of preprogrammed commands. There may be so many preprogrammed commands that AI feels like it is providing a truly human response, but it isn't yet. It's just the emotional version of a mathematical equation.

Art comments on this. Consider the multi-artist intervention Spacecraft Icarus 13. Drawing an analogy between the mythical flight of Icarus, who flew too close to the sun wearing wax wings, which melted and led to his death, and the failed lunar mission, Apollo 13. If an imaginary new space mission, Icarus 13, would set off on a mission to reach the sun, it would necessarily fail and, like Icarus, burn up. Yet this knowledge does not prevent the artistic imagination from thinking about what might be, speculating about the possibility of an alternative future ending through the notion of progress. Despite the complex philosophical, political and historical controversies the idea of progress invites into the discussion, as a forward-looking ideal it offers us the possibility to imagine a future behind today's devotion to the principle of unfettered global economic and technological growth. As science solves the puzzles of magic and fairy tales referenced by Marie Curie, human imagination and artistic inspiration invent new, heretofore un-thought-of novelties to explore, new riddles to solve.

A human with its mouth turned downward at the edges and liquid droplets coming out of its eyes = sad human, therefore my AI response should be to express sympathy.

The next level up for AI is to have an art component built into them. For art is the best way for humans to understand ourselves, and for AI to understand humans. Creators of metaverses have to predict how to beneficially manipulate the emotions of future players. They must think in terms of consciousness.

There is something god-like in our ability as humans now to expand the capability of our lives. While we have not (yet) settled new planets, we have created new worlds that can feel as real as our own. The only difference is that the experience is virtual, not literal. Programming metaverses is a natural extension of the realistic breakthroughs in art that astonished 15th century viewers in their immersive realism.

There is something god-like in our ability as humans now to expand the capability of our lives. While we have not (yet) settled new planets, we have created new worlds that can feel as real as our own. The only difference is that the experience is virtual, not literal. Programming metaverses is a natural extension of the realistic breakthroughs in art that astonished 15th century viewers in their immersive realism.

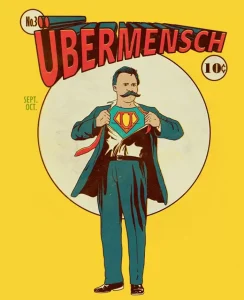

In this way, we embody Nietzsche's Uber mensch. We've transcended what humans were ever capable of doing. Human Capability 2.0. The metaverse = us +.

The key is understanding that we are humans creating alternative realities for the enjoyment of other humans. The virtual world, with millions of people theoretically alone in their homes wearing oversized goggles, may appear to a third party as alienating, lonely. But in fact, it's just the opposite. It is a new way of making interhuman connections. It should never be instead of actual human interactions, but it's provided a new path. The human creative of a metaverse must always have in mind the human users of it.

Matteo Moriconi

_______________________________________

President of the Brazilian Association

of Visual Technology

in collaboration with Dr Noah Charney, Professor of Art History