The Art in Artificial Intelligence

Introduction

by Matteo Moriconi in collaboration with Luiz Velho, Noah Charney and Bernardo Alevato

ArtinAI: INDEX | INTRODUCTION DIGITALLY MANIPULATED ART - PART 1 | ORIGINS OF AI ART - PART 2 | AN ENGINE FOR THE IMAGINATION - PART 3

In 1954, Roald Dahl wrote a short story called "The Great Automatic Grammatizator." It is about a machine that can write an award-winning novel as well as any human, and in just a few minutes. That same year, science fiction writer Groff Conklin called the story "an inspiring fantasy-satire ... an unforgettable bit of biting nonsense." Today, some 70 years later, an equivalent machine system is here and is the talk of the tech world. The combination of machine learning and AI (artificial intelligence) has created software platforms that work like the Great Automatic Grammatizator, writing legible, coherent texts and creating unique images based on prompts. What was once a "fantasy" and "nonsense" is now very real.

In September 2022, Colorado-based artist Jason Allen won first prize in the Colorado State Art Fair. This might not have been particularly noteworthy, had Allen's work, entitled Theatre d'Opera Spatial, not been created by artificial intelligence. Allen had not created the work in the traditional artistic sense. Rather, he entered textual prompts into an AI engine called Midjourney, which then produced the artwork in question as a unique digital image. AI art engines "scrape" the internet for images that are then categorized. When a creator enters prompt words into the software that describe the sort of image the creator would like, then the AI magics into being a new, unique, never-before-seen image, with no elements directly copied from preexisting images, but which includes the style, vibe and content elements called for by the prompt.

Jason Allen's AI-generated art won a prize at the Colorado State Fair (Image credit: Jason Allen via Midjourney)

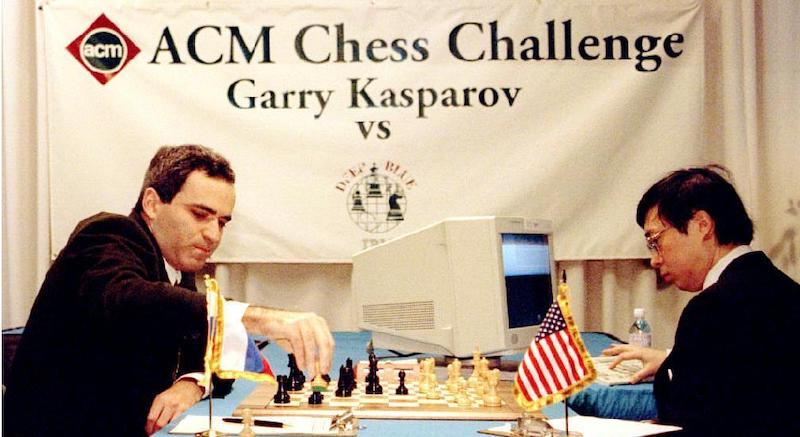

Allen wasn't trying to be sneaky. He was overt that his submission had been created by AI, and it won in the digital arts/digitally manipulated photography category. The headlines that pinged around the globe made it seem like an AI submission had beaten traditional artists in traditional art forms. That's more of a clickbait storyline, like when Deep Blue chess software defeated the world chess number one, Gary Kasparov. But this is indicative of a sea change: AI can make beautiful, interesting art the credit for which goes to the creator, who need not have any artistic proclivities-they just type prompts into a computer.

Some worry that this marks an "end of art," but that bell has been tolled countless times over the centuries. The printing press was also supposed to be the end of art and literature. The camera marked the "end of art." Those with enough understanding aren't worried about traditional art somehow grinding to a stop, although there may be a good deal less business for illustrators and graphic designers. But this revolution does prompt a variety of interesting questions that are more philosophical than anything else.

Can a machine create something, well, creative that is of equal value to what a human conjures up? Can human aesthetics be formalized, categorized and "read" by machines to such an extent that human desires become predictable and easily (and fully) fulfilled by a machine? If so, will humans really need other humans anymore? Is a human element needed to create art that is interesting and moving? Or can generative art, art created by software based on programmed algorithms, be just as "good?" This, in turns, prompts the question of what humans might learn from software-generated art, both about art and about ourselves?

ArtinAI: INDEX | INTRODUCTION DIGITALLY MANIPULATED ART - PART 1 | ORIGINS OF AI ART - PART 2 | AN ENGINE FOR THE IMAGINATION - PART 3