The Art in Artificial Intelligence

The Digitally Manipulated Category (Part 1)

by Matteo Moriconi in collaboration with Luiz Velho, Noah Charney and Bernardo Alevato

ArtinAI: INDEX | INTRODUCTION | DIGITALLY MANIPULATED ART - PART 1 | ORIGINS OF AI ART - PART 2 | AN ENGINE FOR THE IMAGINATION - PART 3

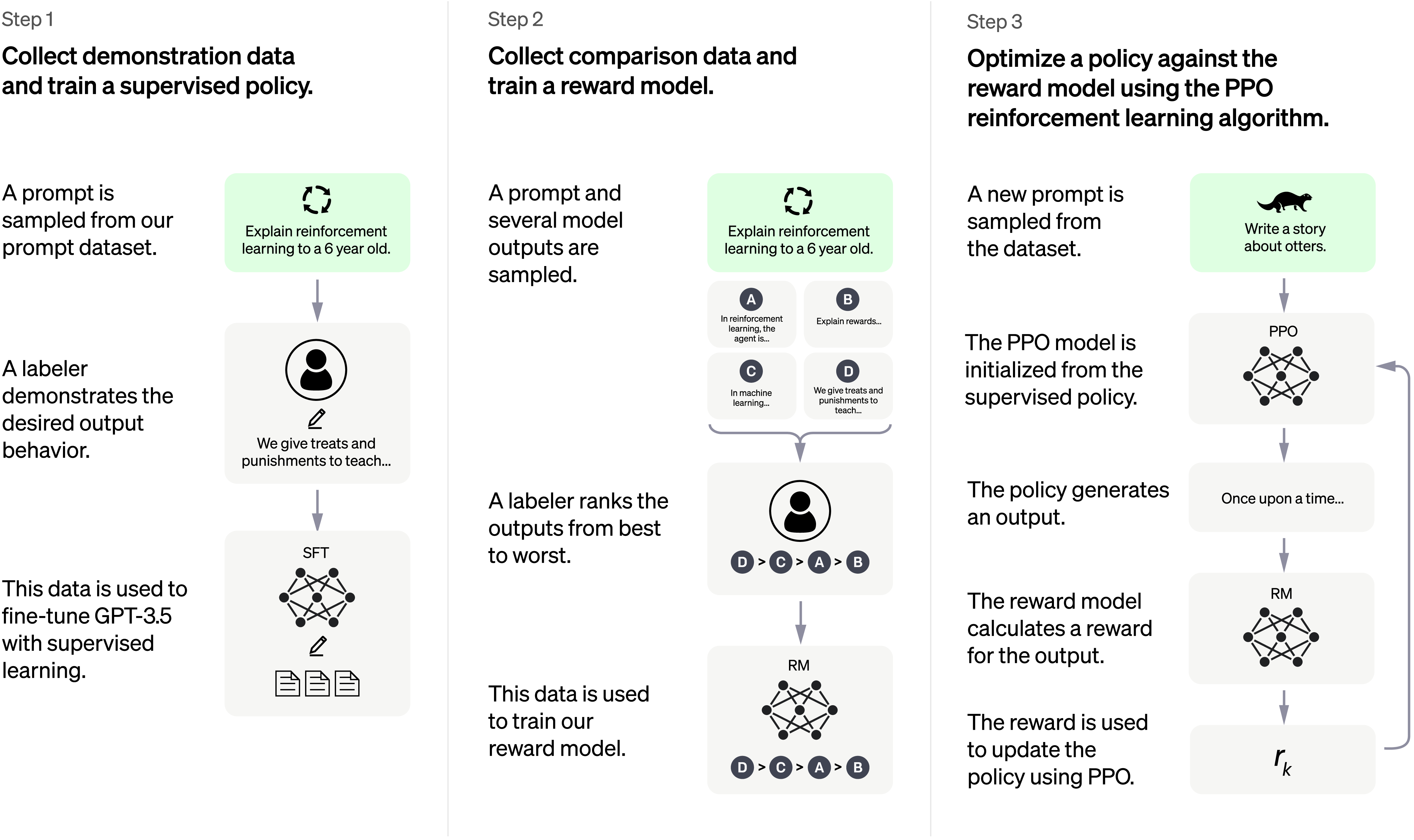

Dall-e, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion and other democratic AI platforms are the talk of the internet these days. They represent a convergence of several technological pillars. On one side, we have technology that evolved for the past decade in its understanding of digital images. For example, if you take a picture today of a glass and a book on a table, technology is capable of recognizing that there are three things within the picture: glass, book and table. That's the identification of patterns using machine learning. Software doesn't just see the whole image, nor does it rely on human-entered metadata (like the human who uploaded the image typing in that it should be categorized as including a glass, book and table). The software can "think" for itself and "read" the image, both for its content and for more ephemeral elements, like its style (is it Cubist, Mannerist, a photograph or a photo-realistic painting).

Another technology that runs parallel to this is that which is used to understand human semantics. ChatGPT and similar software learns how we speak, ask questions, seek answers. It can fully understand the grammatical senses and translate from one language to another using AI.

If you describe something, you apply grammatical rules that help people to understand you. If you say, "I read a book," the grammatical guidelines of English let the listener know that you are talking about the act of reading, as a verb, when someone unfamiliar with English might mishear this as "I red. A book," and think that you are the color red and the book is a separate idea. These rules can also help computers understand. Merging semantics (the study of meaning in language), semiotics (the study of symbols as elements of language), AI and machine learning, you get something unique. Ask AI for a picture of a "wine-dark sea," a famous turn of phrase from The Odyssey, and it will now know that you are using a metaphor, not that you want a picture of a sea made of dark wine.

Semantics and semiotics go hand in hand because you need language to communicate ideas and requests, and you need images summoned up by mentioning words in order to fulfill the request correctly.

It works both ways. Text, words, what we say summons up images in the mind of the listener or reader. But an image can summon up words to describe it. Show a kid a cat, for example. The kid will say, "That's a cat." The kid learned to identify a cat, independent of its colors, shape, size. Articulating "cat," a semantic act, summons up an image of a cat, the semiotic symbol prompted by the word. Computers running sophisticated machine learning systems can pull off this summoning magic trick, as well. The most advanced such system is called an LLM or Logic Learning Machine). Of this, Philip Rosedale, founder of Second Life, wrote:

Philip Rosedale, founder of Second Life

"LLMs are our first contact with alien intelligence, and we got there because memory bandwidth was still too low to allow current hardware to update large neural networks in real time, like our brains do. So instead we found another way: offline training using gradient descent to process a huge corpus of text and yield a fixed model that can then complete text at real-time communication rates. This type of intelligence is completely different than ours: we learn by continuously adjusting synaptic weights in a recurrent network to better match sensory inputs and predict the near future. So now we get to explore this new form of intelligence and find the things it can do differently/better than we can. What an incredible moment in history to be alive."

This LLM creates a parallel in machines for how kids learn. We might consider Midjourney and similar AI engines as the equivalent of Microsoft Paint for a quantum computer-a machine that does not yet exist.

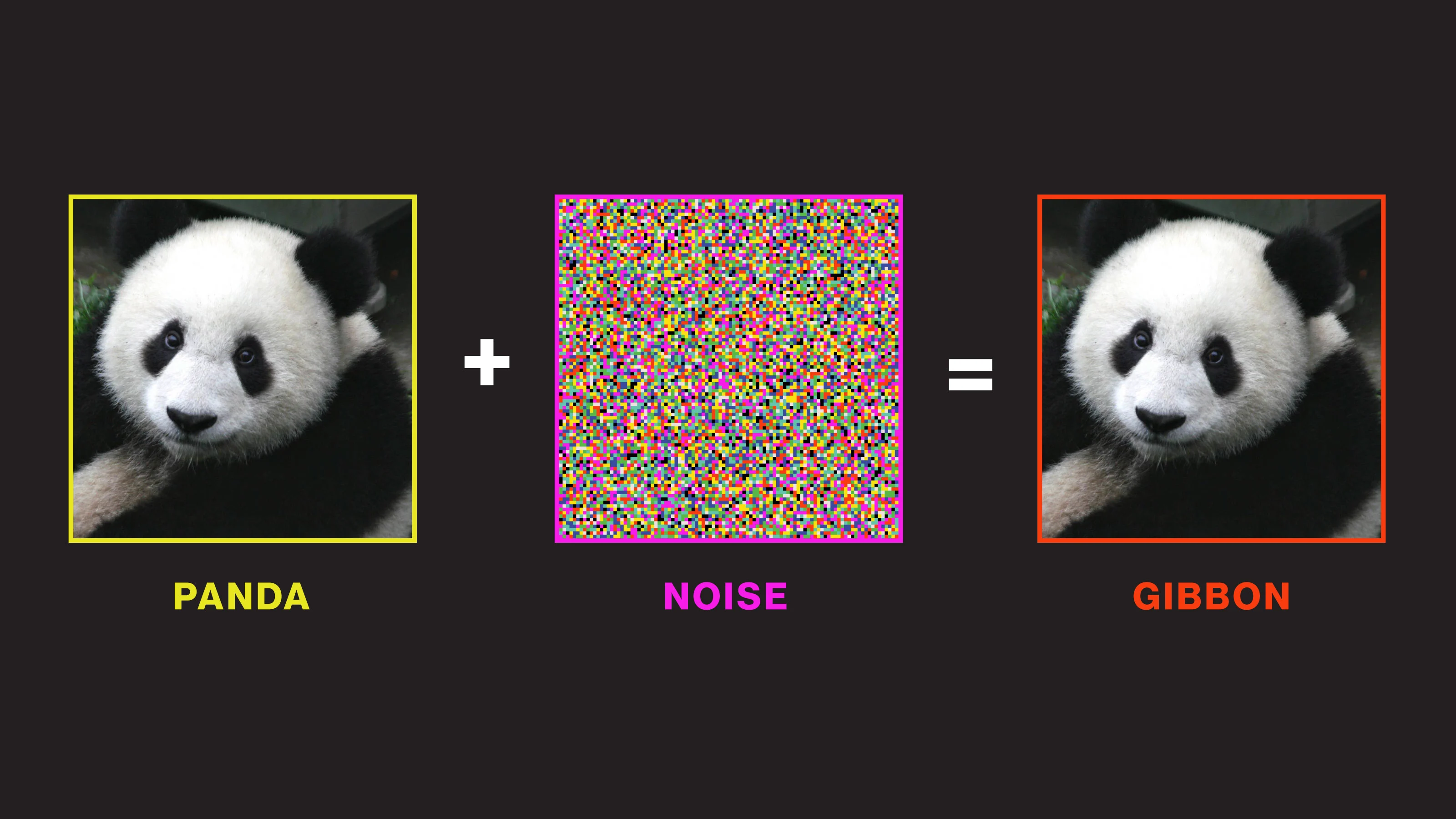

When you describe an image, you are effectively using words as prompts to insert that image in the mind of the listener. This is what you do when entering textual prompts into AI software. The prompts lead to pulling up images linked by category in their metadata (most of which is proactively gathered by the software, not relying on a human to enter it into the description of the image when they first upload it to the internet) out of the "noise"-the immense pool of images culled from every image available online. And each summoning will result in a unique image. If you try to use the same prompt twice, the results will differ. In theory, there will never be an exact duplicate produced from even identical prompts within any AI system.

When you converge this with AI and machine learning to create AI art, you get a powerful summoning potion. Today, you can access a huge amount of data and craft almost anything you want. This data goes through neural computing models, categorized by shapes, forms, colors...all the ways to describe the images within the data. That process creates "noise." This uses classical and non-classical mathematics to gather all the information available in the machine learning process.

When you write or speak something, it's a prompt. This is the "DeNoising process." Your description helps select what you'd like from all that noise. At the moment, only two-dimensional images can be summoned. Three-dimensional will come, and video. But first you must "denoise." If your data set contains a lot of data, then your noise is very rich, like a thick soup. The images you summon up will be based on the noise. Like when you ask a kid to describe a cat, the cat that is summoned from their imagination is one based on all the imagery they've absorbed that they associate with the prompt "cat."

That imagination is, of course, colored by the culture of each child, or anyone who is summoning up an image from a textual idea. One of the objections to much AI art today is that it draws from the quantity of images available online, and that noise comprises mostly Euro-centric themes, imagery, protagonists and artworks. In the future, noise and its data sets may have more importance than it does today, affecting the way that next generations conceive of imagery to accompany ideas. If the noise is full of Caucasian archetypes this might sway how generations think.

For example, searching for images of a "doctor" results in almost exclusively Caucasian middle-aged men. Today we understand that anyone can be a doctor, regardless of race or gender, and you can have a doctor fresh out of medical school or one a week from retirement. But ask an AI engine for a picture of a doctor and you're likely to get only Caucasian middle-aged men in white lab coats, no matter how many times you ask for the generic professional term. AI is biased in favor of whatever imagery exists already in the largest quantity online.

If the future will see greater use of AI not just for creating content based on what we users already think we want to see, but also informing users based on what the AI creates, then this could be a problem, cementing the biases in place online and perpetuating them. If a culture is not well-represented online, represented enough that AI considers it worthy of inclusion amongst all that noise, then those elements of that culture risk disappearing from the popular imagination.

The semiotics side of the matter is where machine learning understands what sort of image you'd like based on what you ask for and how you ask for it. It also learns how you'll speak to it, making requests. Take, for example, an iPhone, which allows you to dictate text messages. Say that you want to send a message to someone with a name that's complicated for a computer to understand, perhaps Mey-Mey. It's uncommon, with an unusual spelling, but once you teach your iPhone the name, by typing it in and rejecting the software's autocorrect attempts, its machine learning understands what you want, that this is a proper name that you want it to write in just such a way. Semiotics is about not only having machines learn human languages, but also learn to adapt to individual uses of languages, since we all have different approaches to how we speak and which names we regularly use.

Machine learning teaches itself what you want when you speak a prompt. This is already normal for us when we use music streaming services like Spotify. We can say "play some good rock music" and, based on what the service has tracked in terms of what we like, what we've asked it to play in the past, what we've taught it by clicking a thumbs-up icon when it plays a song we enjoy, it will play us something from its library that it thinks we'll like. This may be a song it knows we like because we've played it often or given it a thumbs-up, but the machine learning aspect is in full effect when it summons up a song to play that we've never heard before, but which we do like, perhaps it even becomes a new favorite, because the machine has learned how to please us. Spotify does not yet write and record new songs based on what we ask for-that creative AI aspect hasn't yet been made, so we can't yet say "compose me a mashup of Megadeath and Woody Guthrie" and, within seconds, enjoy listening to the brand new composition. But the machine learning aspect is well-established when it comes to music services. The music service pulls out a pre-existing song based on your prompt.

With AI art, the twist is that the system is not pulling out a pre-existing image, thinking or knowing that we'll like it. Instead, it creates a new image, based on the prompts, that we will be pleased with because it fulfills the commission: showing us something that indeed fulfills the prompt request.

This library of images means that anyone, regardless of artistic ability, can use the AI to conjure up stylish images. It has democratized creativity, bringing the products of creative individuals to anyone, regardless of their own artistic training or skill.

Some articles have argued that the quantity of images available online, the noise, is too heavily focused on art of a certain type. There is more "Western style" painting, for example, than Oceanic tribal art available online, so AI is more likely to create more "Western style" images. But this is really a question of what creator requests. If enough people included "Oceania" in their prompts, then more noise in that style would be created as more images fill the internet that adhere to that artistic approach.

Greg Rutkowski

It's been fascinating to see what creators wish to make with AI software. For example, traditional fantasy artist Greg Rutkowski, whose paintings illustrate a Dungeons & Dragons/Lord of the Rings world, is a more popular prompt than Picasso. But this, likewise, isn't a problem, nor is it particularly enlightening, other than highlighting the personal aesthetic preferences of the people using AI platforms, who skew younger, male and tech-savvy, those who have grown up enjoying video games and are more likely to be fans of Sci-Fi or Fantasy than of German Expressionism or Picasso's Blue Period. The audience mirrors the usership of Discord, the tech- and video game-focused chat server that has some 140 million active monthly users (sending about 25 billion messages per month) and which launched just a few years ago, in 2015. It does this quite literally since Midjourney, the most popular AI engine, provides an image generator that is accessed through a Discord chat server. You log into Discord and enter your prompts right there, so they appear in the chat.

ArtinAI: INDEX | INTRODUCTION | DIGITALLY MANIPULATED ART - PART 1 | ORIGINS OF AI ART - PART 2 | AN ENGINE FOR THE IMAGINATION - PART 3