Metaverses of Space

Architecture and the Willing Suspension of Disbelief

This essay is Part 2 of a series on Art and Metaverses,

. For Part 1, on metaverses and the history of art, click here. For Part 3, on metaverses in popular culture, click here.

MANIFESTS: INDEX | ACTIVE PRESENCE | I WANT TO BE A MACHINE | MULTIVISION | THE SMILE OF CHAOS

"We are called to be the architects of the future, not its victims."

Buckminster Fuller.

Metaverses fall into the category of architecture. This may not feel obvious at first, since those who make them program and develop entire worlds, not simply buildings, and they are "built" not of steel, wood and stone but of pixels and code. But a true and deeper understanding of what architecture really is can help us understand where metaverses fit into the history of art. And why they are going from a hypothetical touchstone of sci-fi pop culture to a reality-albeit a virtual one, that looks poised to be the next great leap forward in entertainment and high art.

METAVERSES AS ARCHITECTURE

For creators of metaverses, there are three primary components to consider. Whether the space in which a player, wearing VR goggles, can occupy is a room, a building or a landscape, the areas in which someone can move must be defined. The word "define" comes from the Latin, definire, which means "to bound or limit." Setting up perimeters means establishing where one cannot go, the "walls" around the maneuverable space, as much as what can be done within it.

Step one is to design what metaverse programmers refer to as the "environment." In metaverse terms, this means the spaces which a player can explore-the play area. Within that play area, a designer then incorporates "props," elements that give identity to the space, which can be implements that a user can interact with. The final step is to build a "sphere," it functions like a visual, virtual biosphere. What can be seen beyond the playing field, the "environment," that helps to make a space feel real. This could be a night sky above, trees in the distance, a seascape on the horizon. It is a stage set that is beyond the interactive space but helps to establish it and make it feel realistic. What shifts this all from appearing manmade to feeling real is the naturalistic integration of light and its contrast, shadow.

Accessories within the workshop created for the VFXRio environments on the Spatial.io platform

With this in mind, both the "environment" and the "sphere" are architectural elements. The "sphere" is the background, the "environment" is the defined area of movement and play. In both cases, space functions as an entity. It has a mood that is subconsciously "read" by the player. The "environment" could be a lamplit town square lined with brownstones while the "sphere" beyond it are what we can see through the windows of those brownstone rowhouses. They influence the way a player will feel within the space, before anything actually happens to them, before they even take a virtual step. This also influences how a player will behave. This, in turn, catalyzes the other players.

With this in mind, both the "environment" and the "sphere" are architectural elements. The "sphere" is the background, the "environment" is the defined area of movement and play. In both cases, space functions as an entity. It has a mood that is subconsciously "read" by the player. The "environment" could be a lamplit town square lined with brownstones while the "sphere" beyond it are what we can see through the windows of those brownstone rowhouses. They influence the way a player will feel within the space, before anything actually happens to them, before they even take a virtual step. This also influences how a player will behave. This, in turn, catalyzes the other players.

As architect, inventor and philosopher Buckminster Fuller said, "We are called to be the architects of the future, not its victims." He envisioned a world in which "industrialization trends swiftly and altogether transcendentally to man's conscious planning." In other words, human invention shapes the future and technology possesses absolute potential.

As architect, inventor and philosopher Buckminster Fuller said, "We are called to be the architects of the future, not its victims." He envisioned a world in which "industrialization trends swiftly and altogether transcendentally to man's conscious planning." In other words, human invention shapes the future and technology possesses absolute potential.

"The Shining" Warner Bros.

FILM SETS AS PROTOMETAVERSES

Stanley Kubrick makes for an apt film parallel. He used to craft his spaces-the sets for his films-long before actors arrived, building emotion through set design, which is its own type of temporary architecture. In The Shining, the haunted hotel is as much a character as those played by the actors within it. The "environment" consists of the rooms in the hotel and the hedgerow maze beyond it. That was all-part of the plot is that everything else is snowed in, locking the characters out of the rest of the world (the "sphere") and into the "environment." The space is introduced, reflecting its own "personality," long before the story develops.

Movie Director Federico Fellini on the set of Casanova on July 10, 1975

Consider Cinecitta, an elaborate film studio consisting of numerous, alterable, enormous stage sets-99 acres' worth-on which films were made. It was a city (as the title, which translates as Film City, suggests) dedicated to make-believe spaces and movies. It was built by Mussolini during Italy's Fascist period, inaugurated in 1937, under the slogan "Cinema is the most powerful weapon."

The films initially made there were meant as pro-Fascist propaganda, but thankfully those are largely forgotten. It is best known for what emerged from it during the era of Italian director, Federico Fellini, working in the 1950s on many of the estimated 3000 films made there, including 47 Academy Award winners. Decades before the advent of the metaverse, it was a place where alternative universes were designed, built and interacted with by actors, in order to "transport" the audiences of their films to another time and place through the magic of cinema. A metaverse is an artificially created space in which a continuous narrative can take place. Film studios create proto-metaverses which are experienced through the films made in them, rather than by virtually inhabiting the spaces, as can happen today. The contemporary metaverse is one you, the viewer, can enter and interact with.

Vitral de la Iglesia de Hamelín

The Pied Piper of Hamlin is a metaverse programmer. People will follow his "song" if he plays it well enough. Audiences are the children that are drawn to follow him, haunted by the art he creates. The quality must be high enough, and then it becomes a catalyzer. What the camera obscura did to help Renaissance artists more easily and reliably recreate a reflection of reality in their paintings, metaverse programming does for virtual architectural spaces. Metaverse spaces are the new catalyzers. We've seen in the past how an artist can illustrate a philosophy. Surrealist painter Rene Magritte catalyzed French philosopher Michel Foucault, as seen in Foucault's book on Magritte's painting, Ceci n'est pas une Pipe. Now metaverse programmers are the artists embodying theories, like Jean Baudrillard's 1981 "Simulacra and Simulation," which theorized metaverses and avatars long before computers were capable of creating them.

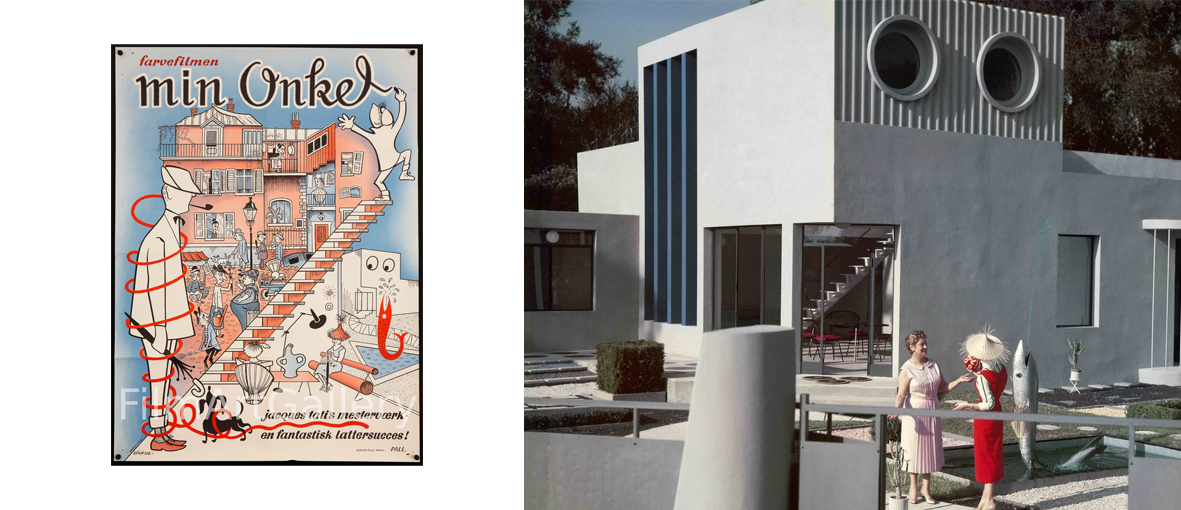

(1958), by Jacques Tati

What viewers tend to remember most about Jacques Tati's 1958 film, Mon Oncle, is the house in which the 9-year-old protagonist lives, Villa Arpel. It was built expressly for the film, a house meant to be designed for style rather than function-the opposite of the houses in which most of us live. Tati once said, "Geometric lines do not produce likeable people," and so Villa Arpel is meant to surprise and delight with its charming a-functionality: the furniture is delightful to look at up hard to sit on, the appliances are so loud you can barely hear yourself, steppingstones are spaced ludicrously far apart. It is a fantasyland.

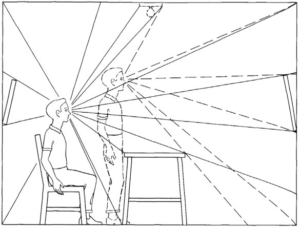

Sampling the convergent rays at multiple vantage points. Adapted from Gibson (1966).

Tati was more interested in how real buildings can influence the people who live there, and the extension of James Gibson's "ecological theory of perception," rather than trying to predict how humans might live in the future. Gibson's theory is one in which the observer "productively engages with the environment through movement and visual perception...the environment is no longer perceived as a seen object or a 'thing'" but as "an affordance of a stimulus which holds the capacity to offer meaning to the observer, thus stimulating the observer to productively respond and engage with the environment." Gibson developed this theory while working with fighter pilots during World War II, but he may as well have been writing about metaverses.

They can also be filled with objets à réaction poétique (objects that provoke a poetic reaction). Consider the 1884 novel, Against the Grain, by J. K. Huysmans. It tells of an elderly eccentric man who determines that people are the worst and decides to build a house into which he can retreat in his old age and never emerge. But the house must have everything in it he could ever want, including details and objects that will spark his sense-memory of favorite moments of his past, so that he need only use them or look upon them to be virtually transported to key points in his biography.

Each of these items- from his pet tortoise whose shell he has encrusted with jewels, a garden of poisonous tropical plants, and an array of scents that he smells in specific orders, recreating scents that provoke flashbacks of moments and people he wishes to remember-are like "props" in a metaverse. The metaverse designer can place anything, anywhere, without thought for cost or logic, since all of it is just pixels and code.

This was taken to a new level by the director, Alejandro G. Inarritu in his Academy Award- winning 2917 film, Carne y Arena. In it, he used virtual reality to humanize refugees by allowing audiences to briefly enter the world of refugees, taking them on as avatars, virtual characters who they "play." It is the literal version of the idiom "take a walk in someone else's shoes." While some worry that virtual reality will be dehumanizing, since the interactions with other humans are through the medium of computers and virtual representations of each other, this is a strong counterargument that VR can indeed be humanizing.

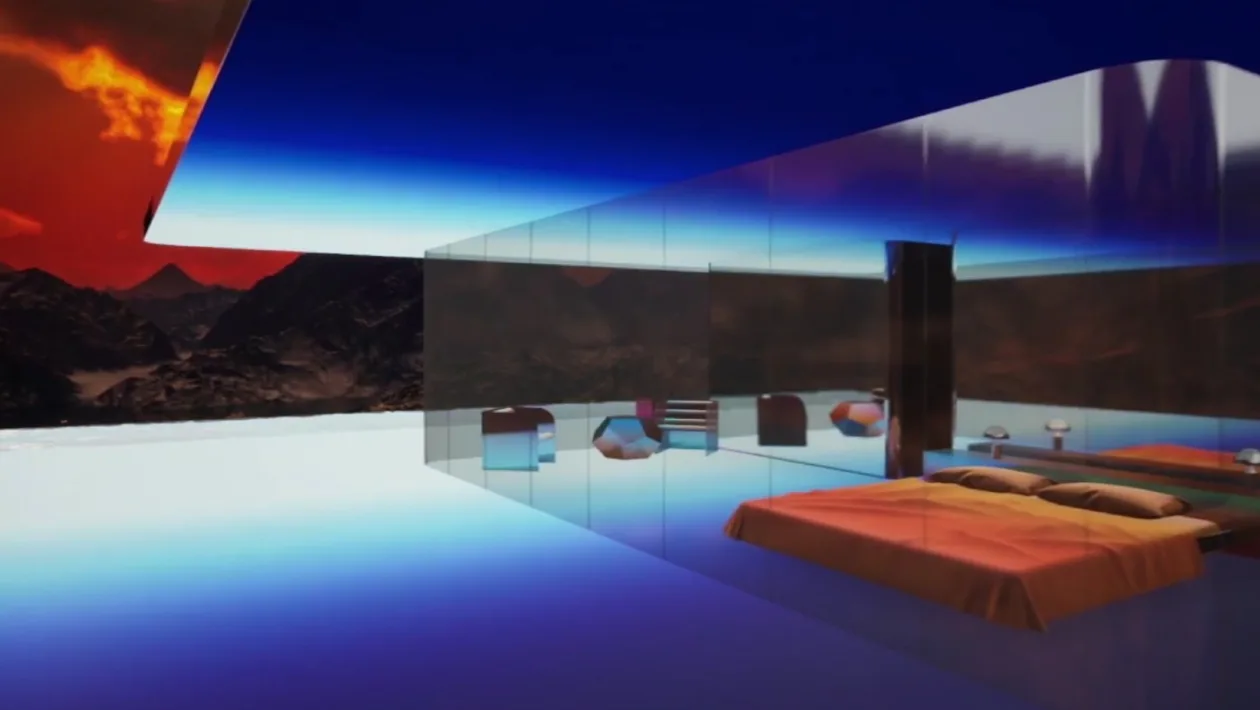

Mars House – the first NFT digital home – sells for $512,000

METAVERSE AS LITERAL ARCHITECTURE

In March 2021, digital artist Krista Kim sold the first digital house as an NFT (non-fungible token) for over half a million dollars. It was a metaverse, a 3D digital space through which a player, wearing VR goggles or using an AR (augmented reality) app, can move and interact. But it is in the form of a house, called Mars House. Now the buyer controls access to it-either keeping it for himself only or permitting others to explore it. It was created during the Covid-19 lockdown in 2020, allowing Kim the chance to play with humans "traveling" through a virtual experience even when their bodies are not permitted to physically leave the house.

Software that permits the creation of virtual spaces is popular with children and adults alike. Minecraft is, far and away, the most popular video game ever made, and it consists largely of players using digital blocks to build structures-like a digital game of Lego. Occupy White Walls provides the same function but in a more realistic manner and with the focus on players designing and building their own art galleries, then filling it with digital replicas of real artworks.

Software that permits the creation of virtual spaces is popular with children and adults alike. Minecraft is, far and away, the most popular video game ever made, and it consists largely of players using digital blocks to build structures-like a digital game of Lego. Occupy White Walls provides the same function but in a more realistic manner and with the focus on players designing and building their own art galleries, then filling it with digital replicas of real artworks.

From architects of real buildings to those of cinematic stage sets and now to programmers of virtual spaces, metaverses represent the latest vanguard in the union of human interaction with space and the willing suspension of disbelief.

Matteo Moriconi

_______________________________________

President of the Brazilian Association

of Visual Technology

in collaboration with Dr Noah Charney, Professor of Art History