MULTIVISION MANIFESTO: REFLECTIONS OF THE HUMAN IMAGINATION

MANIFESTS: INDEX | ACTIVE PRESENCE | I WANT TO BE A MACHINE | MULTIVISION THE SMILE OF CHAOS

Sometime in the 4th century BC, Plato wrote on an allegory of the human condition that feels startlingly prescient today. He imagined that human existence was not actually happening to us. Instead, we perceived a "shadow" or simulation of reality filtered through our senses. His analogy was that we humans were situated inside a cave with our backs to the entrance, our faces looking at the cave's rear wall. Light outside the cave shone on reality-say, a bison walking past the cave entrance-and cast a shadow of that reality onto the wall before us. We could see the shadow of the bison, not the bison itself but a holographic projection of it.

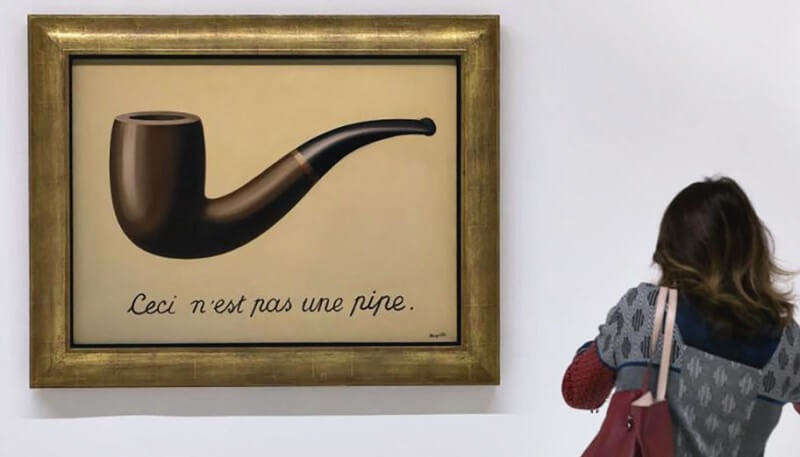

This Platonic "Allegory of the Cave" has been adopted by all manner of fields and thinkers. Renaissance painters believed that their paintings, particularly of holy scenes, were not showing us reality but a painted "shadow" of reality. A picture of the Holy Family by Mantegna did not allow us to actually see Mary, Joseph and the baby Jesus, but a simulation of them. The Belgian Surrealist painter, Rene Magritte, commented on the same concept four centuries later, in his famous painting, The Treachery of Images. It shows a painting of a pipe, including the painted words (in intentionally incorrect French), stating that "This is not a pipe." He was right. It's not a pipe. It's a painting of a pipe. The "shadow" of a pipe, as Plato would have called it. This painting and its concept were so resonant with great thinkers that philosopher Michel Foucault wrote a whole book about it.

It's an idea that just won't go away, as is the case with all of mankind's truly revolutionary conceits. It inhabits all forms of art. In music, Vivaldi sought to create auditory projections of the four seasons and Mussorgsky wished to paint mental pictures of imaginary pictures in his famous piece, "Pictures at an Exhibition." The Brazilian composer, Heitor Villa Lobos, sought to use music to help the listener "see," in their mind's eye, a virtual, immersive landscape with a train winding through it in his "The Little Train of the Caipira - O Trenzinho do Caipira" toccata. They echo and feel ever fresh.

The sci-fi film, The Matrix, transports the same concept to the digital world, in which humans exist in a computer simulation of reality that is so vivid that they don't know it's a simulation (an idea first published in philosopher Jean Baudrillard's book, Simulacra and Simulation). But such a simulation could only be made by humans. The technological paradox of MC Escher's 1948 Drawing Hands comes to mind. A drawing of a hand is drawing a drawing of the hand that is drawing it. Just writing that sentence makes one's mind melt. And so it can be that a metaverse that appears as real as the real world could only have been created by someone in the real world-but who is to say that they are not, also, a simulation and they just don't know it?

When the first works of art were created, paintings on cave walls, our prehistoric ancestors were creating their own alternative reality. The bison they drew on the wall was their "projection" of the real bison they hunted outside. Pablo Picasso once said, in reference to paintings in a cave called Altamira, "After Altamira, all is decadence." This was art for prehistoric man: capturing a vision of the real, controlling it and projecting it where they pleased. While it was a cave wall 34,000 years ago, today it is a 4K computer monitor.

The concept of a cave that is so real that we don't realize it is a simulation was made manifest in physical form in 2015 in France. The Caverne du Pont d'Arc is a precise 3D printed replica of the ancient Chauvet cave, which contains cave paintings so fragile that human breath would cause them to disintegrate, and so the real cave is closed to the public.

Recognizing the Platonic connection, Werner Herzog made a documentary film in 2010 of the actual Chauvet cave, where he was permitted to film for just a few days, called Cave of Forgotten Dreams. None but a few scholars can ever visit the real Chauvet cave. Instead, if we wish to experience it, we must watch Herzog's documentary film and see a digital "shadow" of it or visit the Caverne du Pont d'Arc and see a 3D printed physical "shadow."

Are these "shadows" real or fake? It depends who you ask and how someone conceives of it. Ask almost anyone what they see in Magritte's The Treachery of Images and they'll say "It's a pipe." Pablo Picasso said, "Art is the lie that reveals the truth," the truth about how we humans think. That's the cognitive trap into which Magritte wishes to throw you.

The term "uncanny valley" is used to describe objects or phenomena that mess with our minds by straddling the liminal zone between what we perceive as real and what we see as an illusion, something manmade and artificial. Modern robots can feel so realistic that we can hardly tell the difference. Contemporary thinkers wonder if the difference matters at all. If most of humanity is happier inside The Matrix then do they want to know that it's all an illusion?

This is particularly relevant today, when the internet is populated with alternative reality options. We can slip on VR goggles and feel that we are actually seated in a football stadium, looking left and right and seeing other Virtual Reality spectators as they choose to appear-as curated digital avatars-all enjoying this video view of a live football game played by real human beings who may be on the other side of the world. The term metaverse refers to virtual spaces that can be visited online, often so naturalistic and elaborate that they feel real.

Metaverses can be populated with digital images that we consider and describe as if they were real. You can buy real estate in Decentraland, one such online metaverse, and set up a virtual art gallery displaying NFTs, non-fungible tokens, which are unique digital files (like jpegs or mp3s) written into the blockchain so that we feel we have ownership of them. You can't buy Escher's real Drawing Hands, but you could buy an NFT of it and set it up in your virtual gallery in Metaverso.

Much of this is about tricking a mind that is happy to tricked. We can confound our depth perception by covering one eye. We can give the illusion of virtual reality by wearing special glasses. We can buy a robotic dog and feel that we have a real companion-studies have shown that elderly who keep one of these robotic dogs enjoy the benefits of real company, even when there is no other organic being near them.

The problem with artificial intelligence (AI) and simulations, whether robotic or digital, is that they lack the basis for truly understanding human nature, particularly suffering. They can be programmed by humans to respond in human-like ways, but all they can do is mimic back what the programmer tells them to. They cannot empathize.

But that is where art comes in. Art has long been seen to mirror the human condition. Whether it's Shakespeare's Hamlet or Melville's Moby Dick or Picasso's Guernica or Mozart's "Requiem" or Villa Lobo's "The Little Train of the Caipira - O Trenzinho do Caipira," we feel that great art speaks to us, both collectively as humans and as individuals, where we project our personal situation and mood onto the art and see our own reflection in it. Deep thinking about the metaverse, virtual reality and the potential loss of the human side of the equation is important. It can help to identify future trends, as each new horizon of technology, which ostensibly is invented to solve problems, also opens up new sets of problems that need to be solved. Each new set of problems is simultaneously a new opportunity to solve those problems. It also provides insight into our social responsibility.

We must be aware of the consequences of the technology we so eagerly and rapidly create. Most of the consequences are beneficial, but for every life-saving medicine there are unwanted side effects against which we must be forearmed. All of this is a call for striking the optimal balance in what technology allows and what it cannot (yet) incorporate, or even what it closes off for all the doors that it opens. Whenever possible we must inject soul into the virtual worlds we create.

In order for our humanity to survive and perhaps even thrive, we must marry the human elements of art with the illusory delights and functions of the virtual.

Matteo Moriconi

_______________________________________

President of the Brazilian Association

of Visual Technology

VFXRio Live: www.vfxrio.com.br

The Multivision Manifesto: Reflections of Human Imagination is the result of continuous and intense exchange of ideas with VFXRio collaborators Liana Brazil and Luiz Velho. The Manifesto proposes a revisitation of Marshall McLuhan's ideas published in his book "Understanding Media - the extensions of man".