The Deep Art History of Metaverses

Metaverses in the Art of the Past

This essay is Part 1 of a series on Art and Metaverses,

. For Part 2, on metaverses and architecture,, click here. For Part 3, on metaverses in popular culture, click here.

MANIFESTS: INDEX | ACTIVE PRESENCE | I WANT TO BE A MACHINE | MULTIVISION | THE SMILE OF CHAOS

""The object of art is not to reproduce reality, but to create a reality of the same intensity."

Alberto Giacometti

Beeple' s auction by Christie's sold for $69 million.

INTRODUCTION

One might imagine that metaverses are a new phenomenon. The idea of creating a virtual world that one can inhabit, interact with, move through, perhaps using VR goggles, is of the moment. VR goggles themselves are a relatively new invention and the ubiquity of them, available from numerous producers at affordable prices, is only a few years old. It was not long ago that barely anyone knew what an NFT was. Now it is a household term. NFTs began as virtual items that could be acquired for real money to be used by your characters, avatars, in video games. Now NFT art has become so collectible that a single work was sold for $69 million.

The term "metaverse" is new-it was coined in the 1992 science fiction novel Snowcrash by Neal Stephenson. It means a network of three-dimensional virtual worlds that permit social interaction with other virtual occupants of those worlds. Its etymology combines the Greek "meta," meaning "beyond" and an abbreviation for "universe." Even the name implies a sort of inter-world travel. In the recent past it was theorized as a future invention in which humans in the real world could inhabit a parallel single, universal virtual world that would allow for interconnection and social dynamic, but free from the constraints of physics and biology. You could create avatars of any sort, with any type of power you could imagine. That universal, single metaverse remains a future concept, but technology has now allowed for the creation of numerous stand-alone metaverses, which might be best understood as planets in an internet solar system. One can visit Decentraland or the metaverse created by VFXRio, and even take virtual objects-NFTs-with you between them, but they are not, as yet, seamlessly interconnected. The internet equivalent of a spaceship flight, from one website to another, is required to move between them.

With this in mind, it's worth asking just how new metaverses are, both in concept and in actuality. The answer is that they are a lot older than you'd think, and they have been present, in partial and varied forms, for ages.

This three-part essay will take a look at the history of metaverses. Part One examines metaverses in the history of art and thought. Part Two looks at how popular culture pulled audiences from outside the entertainment box to deep inside it, as well as how and why science-particularly virtual reality (VR) and artificial intelligence (AI). Part Three looks at humanizing avatars, virtual versions of ourselves. Now, there are virtual worlds as expansive and elaborate as our own real world, but with the potential to be more so, because they can be programmed, expanded and bespoke tailored, through advances in programming and technology, into anything and everything we might desire. What unifies all the themes we will discuss is the requirement of a willing suspension of disbelief on the part of the user, whether they choose to engage with creations in our tangible world (painting, sculpture, literature) or virtual reality creations. There are two components at work assisting the user/audience in their first willingness, then delight in suspending their disbelief and engaging fully with the creation: science and art. While scientific advances have skyrocketed in capability and power, art, in its traditional sense, remains requisite because technology cannot feel. It must turn to the strengths of art to give artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual reality (VR) their anima, or soul.

IMMERSIVE ART HISTORY

How immersive is the viewer's experience? How transportive? That is the key factor to determine the success of virtual reality environments. We often speak in terms of "getting lost" in a good book or the "escapism" of binge watching a favorite TV series. This is about temporarily forgetting your quotidian life and allowing yourself to accept the imitation of reality that you choose to engage with. That you can choose is, in itself, empowering, because not all of us have such power to choose when it comes to our real lives. That you remain at least rationally (if not emotionally) aware that the virtual reality is just that, virtual and not real, means that your rational mind knows that you are safe. Whatever happens in the virtual engagement, however realistic or potentially frightening, is walled off by the knowledge that it is not real. This explains the appeal, for instance, of horror films and video games. In real life, it would be thoroughly unpleasant to be chased by a chainsaw wielding zombie. If you know that it's a movie or a Resident Evil game, then it can be a fun thrill.

This voluntary immersion is described in the theory of theater as "willing suspension of disbelief." As with so many ideas important to art and life today, the earliest writer we know of on the subject is Aristotle. He used the idea to explain how audiences can be so emotionally moved while watching a theatrical play. Their rational minds know that it is all staged, fake. They bought a ticket and are seated in a theater, a space for make-believe, and watch actors who they know by name wearing masks and pretending to be people, even monsters and gods, that they are not. Yet, audiences would laugh and weep and shudder as if it was all really happening. He explained that audiences ignore the unreality of what they see, effectively choosing to ignore their rational mind, in order to better enjoy the experience. To achieve what he called "catharsis," the purging of emotions through experiencing art.

This idea was picked up on by the poet and philosopher, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in 1817-he was the first person to coin the phrase "willing suspension of disbelief." He wrote of how a good writer could imbue a fantasy with "human interest and a semblance of truth."

This has long been the goal of formal art-art that is meant to resemble the real world. Through the Renaissance, most European art sought to achieve ever greater levels of realism. The idea that one could not tell the difference between art and reality was the ultimate triumph. But this was no Renaissance invention. It was rather a rebirth (that is what the word "Renaissance" literally means) of interest in the classical world.

This has long been the goal of formal art-art that is meant to resemble the real world. Through the Renaissance, most European art sought to achieve ever greater levels of realism. The idea that one could not tell the difference between art and reality was the ultimate triumph. But this was no Renaissance invention. It was rather a rebirth (that is what the word "Renaissance" literally means) of interest in the classical world.

The ancient Roman historian, Pliny the Elder, wrote on how Classical Greek art placed an emphasis on naturalism, on the ability of a painter to paint in such a realistic manner as to be able to trick people into thinking that they are seeing something real. He describes a competition between Zeuxis and Parrhasius, supposedly the two best painters of 4th century BC Greece. Zeuxis created a painting of grapes that was so realistic that a bird flew over to the painting and tried to take a bite of the painted grape. Thinking that he had the competition in the bag, Zeuxis headed over to Parrhasius' studio and saw a painting there, covered by a curtain. He asked if Parrhasius would pull the curtain aside, so he could see what he had painted-only for Parrhasius to reveal that the curtain was the painting. The conclusion is that Zeuxis is a brilliant painter, because he was able to fool an animal, but Parrhasius won the contest, because he was able to fool a human.

This can be seen in the marvelous paintings of Petrus Christus, such as his arresting Portrait of a Carthusian Monk (1444). In a refence to the Parrhasius parable, the monk is portrayed as if in a window with a small room visible behind him. The frame appears to be like a windowsill. But the frame isn't really a frame-it's painted. And at the bottom of the painted frame, there is a fly that we viewers can hardly resist reaching out to whisk away. But, of course, it is a painted fly. We have been tricked and are delighted for it. His 1449 A Goldsmith's Shop plays with us viewers, too. A couple stands inside the shop, chatting with the goldsmith, who is seated at his workbench, facing out towards us as we look at the painting. A convex mirror perched on his workbench reflects the street scene outside and a pair of men looking into the shop-us.

15th century humanists, like Marsílio Ficino, were so taken with the rediscovered ancient (primarily Greek) philosophy texts for which scholars hunted in wayward monasteries and dusty libraries that they wound up adapting the ideas they found there and syncing them with their Christian world and belief system. A successful painting, it was argued, was like a window through which you could see the perfection that exists in Heaven. Raphael's religious paintings try to create a virtual reality view of Heaven, populated by perfectly beautiful, nearly identical figures living in peace, grace and balanced harmony. Raphael painted the happiest crucifixions one could imagine-without emotional or pain, just poses. Each of his figures, whether male or female, wear matching faces, sometimes with beards added for the men, but otherwise indistinguishable. But Raphael would have argued, according to Neo-Platonic thought (a new, Christianized theory based on Plato) that it did not matter if anyone ever looked at his paintings. They were great works of art even if they existed in a vacuum. Whether or not they were experienced was irrelevant.

15th century humanists, like Marsílio Ficino, were so taken with the rediscovered ancient (primarily Greek) philosophy texts for which scholars hunted in wayward monasteries and dusty libraries that they wound up adapting the ideas they found there and syncing them with their Christian world and belief system. A successful painting, it was argued, was like a window through which you could see the perfection that exists in Heaven. Raphael's religious paintings try to create a virtual reality view of Heaven, populated by perfectly beautiful, nearly identical figures living in peace, grace and balanced harmony. Raphael painted the happiest crucifixions one could imagine-without emotional or pain, just poses. Each of his figures, whether male or female, wear matching faces, sometimes with beards added for the men, but otherwise indistinguishable. But Raphael would have argued, according to Neo-Platonic thought (a new, Christianized theory based on Plato) that it did not matter if anyone ever looked at his paintings. They were great works of art even if they existed in a vacuum. Whether or not they were experienced was irrelevant.

CONTROLLING LIGHT

Raphael's paintings have little drama and much of this is down to their overall lighting scheme. There is not much shadow, they appear to take place in the light of midday, and this means that much of the potential for drama is stripped away.

Raphael's great rival in Rome, Michelangelo, created the illusion of controlled spotlighting when he painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Not only was this revolutionary in terms of illusionism but also when we consider the experience of the viewer. Today, the Sistine Chapel is a flood of tourists jostling for space and craning their necks skyward to see the ceiling. But when it was finished in 1512, it was accessible only to Vatican clergy and invited guests. To them, it was walking into another world. It was immediately the most talked-about artwork to visit in Rome, perhaps in Europe. And it spread out across a vast ceiling, telling a series of biblical stories the viewers would have been familiar with, but relating them according to Michelangelo's own rules of how and what to see. It was a metaverse unto itself, where the creator-in this case a painter rather than a programmer-could determine that the people he painted would possess musculature that could not exist in real life, and pose them in contortions that were either unrealistic or impossible, only existing-and working beautifully-in the painted world he created. Before anyone had heard of graphic novels or films, this ceiling, divided into "panels" of action sequences, like pages in a graphic novel or scenes in a film, allowed for a form of expansive story-telling that no single painting could contain.

The leading painter of Rome after Raphael and Michelangelo, Caravaggio, was a wielder of light and darkness. He championed a technique called chiaroscuro, meaning the play of light emerging from darkness. Caravaggio used what we might describe as spotlighting, a revolutionary technique that brought tension, mystery and intrigue to his paintings. To look at his work is to see shadows even more than the light required to create them. A world without shadows feels unreal.

He also played a game in which he would mirror his painted light to match whatever natural light shone on the painting, based on the architectural space it would occupy. His first famous works in Rome were the Saint Matthew Cycle (1598-1599), three paintings for a chapel in the Roman church of San Luigi dei Francese. In his Calling of Saint Matthew, he paints light flowing in from the top right corner of the painting, over the shoulder of Jesus, who indicates to an as-yet-unaware Matthew that he should join him as an apostle. Caravaggio did this because a clerestory window (a plain glass window to let in light) in the chapel would allow sunlight to flow in from the same point, melding the natural and painted light, creating an illusion of not quite being sure where the real world ends and the painted world begins.

VR goggles are equipped with light modules that help the user willingly accept that suspension of disbelief. Without proper, naturalistic light (and its accompanying shadows) an artwork will be unconvincing. The light projected into your eyes using VR goggles is a modern technological manifestation of Aristotle's concept of how we see. Aristotle postulated we see by emitting beams of light out of our eyes that bounce back off of what we see, reflecting back into our eyes, at which point our minds process that reflection. The eye as a mirror. Aristotle's idea is not actually how we see, biologically, but it was prescient in imagining how we see in virtual reality, with light projected onto our eyes through the VR goggles. Artists and architects use light to fill space and shadow as a boundary, border and outline that defines edges. If light is projected onto our eyes when it comes to VR, then we might wonder if we are outside or actually inside the artwork.

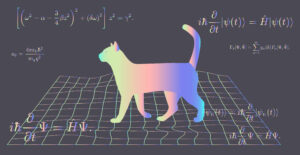

This game of whether the viewer is in the artwork or not was taken to a higher level during the Baroque period (circa 1600-1700). Gian Lorenzo Bernini was among the first artists to recognize that the viewer was requisite to the successful completion of an artwork. If the world's greatest masterpiece exists but no one can ever experience it, then it has no value and one might ask whether it really exists at all, if it can never be experienced? This is a creative equivalent to Schrodinger's Cat: the supposition that a cat may be simultaneously dead and alive, in theory, if we cannot check on its status for certain. Imagine a cat inside a box that also contains a radioactive poison. If a radioactive particle decays, the poison will be released and kill the cat. But if we view the box from the outside, we cannot know if the particle has decayed. So until we check, until we experience for ourselves, the cat remains both dead and alive in theory (though of course not in practice).

This game of whether the viewer is in the artwork or not was taken to a higher level during the Baroque period (circa 1600-1700). Gian Lorenzo Bernini was among the first artists to recognize that the viewer was requisite to the successful completion of an artwork. If the world's greatest masterpiece exists but no one can ever experience it, then it has no value and one might ask whether it really exists at all, if it can never be experienced? This is a creative equivalent to Schrodinger's Cat: the supposition that a cat may be simultaneously dead and alive, in theory, if we cannot check on its status for certain. Imagine a cat inside a box that also contains a radioactive poison. If a radioactive particle decays, the poison will be released and kill the cat. But if we view the box from the outside, we cannot know if the particle has decayed. So until we check, until we experience for ourselves, the cat remains both dead and alive in theory (though of course not in practice).

When it comes to art, the greatest work ever created does not, in theory, exist, if no one can view or engage with it. Bernini welcomed the idea of the viewer as a necessary participant in his artwork and carefully stage-crafted his sculptures to manipulate what the viewer could see. Bernini's work includes what today we might call art installations: multimedia chapels that included sculpture, painting, architecture, mosaic and carefully controlled lighting-similar to what Caravaggio did in painting a generation before Bernini, likewise in Rome. For instance, in Tomb of the Blessed Ludovica Albertoni (1675), Bernini has installed a hidden clerestory window, tucking it behind an architectural element so that the sunlight that poured through it would appear to come from a divine or magical source, since the window itself was hidden. Is the source of light natural or divine? Until we check we cannot know, and the answer, according to Schrodinger, might be "both."

WINDOWS AND MIRRORS

Games with windows and mirrors that blur the boundary between viewers of an artwork and those portrayed within it, effectively pulling us from the external audience into the art itself, can be found in many famous works. Jan van Eyck's 1434 Arnolfini Wedding Portrait shows a couple taking their wedding vows in a bedroom. Flemish tradition required reciting vows before two witnesses in order to legally marry. In the convex mirror at the back of the room, we can barely see the blurred reflection of two men, one in a red turban, one in blue. It could be us, we viewers standing outside the plain of the painting looking at it. But it is also a self-portrait of the artist, Jan van Eyck (known for wearing a red turban) who includes this reflection of himself as one of the two witnesses. He even signed the painting prominently-this was unusual as it wasn't until the 19th century that artists regularly signed their work. What he did was sign his presence as witness to the marriage. The painting serves as proof-this is why it is often called The Marriage Contract.

Including convex mirrors is an inside joke for artists. Convex mirrors were less expensive than apartment ones during the Renaissance and they were a staple of artist studios. Artists would use them to paint self-portraits, of course, but also to frame other subjects they would paint. In order to select the composition for a portrait of, say, a horse, an artist would look at the horse through its reflection in a mirror, rather than directly at it. This is similar to a film director "framing" a scene by looking at it through the camera lens rather than at the actors directly.

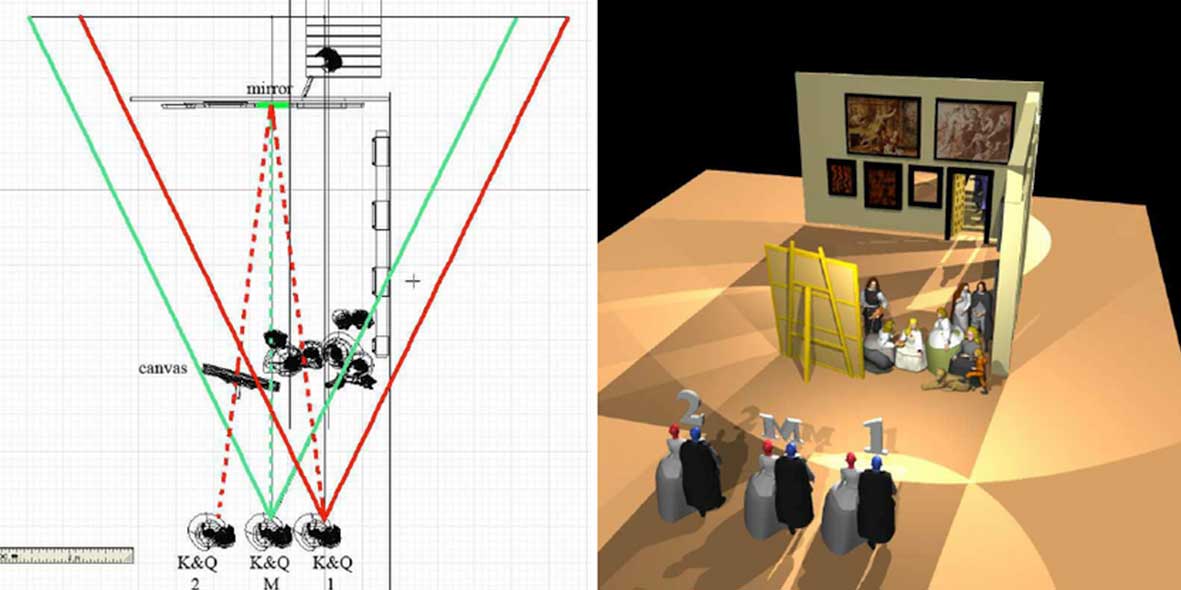

Las Meninas, 1656 (detail) by Diego Velázquez

This framing game was taken to a higher level in Diego Velazquez's Las Meninas (1656). In this complex riddle of a painting, we see Velazquez painting the portrait of the king and queen of Spain, while their daughter, the Infanta, looks on, surrounded by her handmaidens (that is what las meninas means) and other companions. But the infanta and Velazquez seem to look directly at us, the viewers. And Velazquez stands before an enormous canvas, as big as the canvas on which Las Meninas itself is painted. So is he capturing himself in the act of painting this very painting? Why, then, is he looking at us? In fact, he is probably looking at a mirror. Imagine if the surface of Las Meninas were a one-way window of the sort used in police suspect lineups. To those on one side, the window appears to be a mirror reflection. From the other side, we can see through it. Just to add to the mix, in background there is either a mirror or a painting of the king and queen. Are the king and queen standing where we are, being looked at by Velazquez and the Infanta? Or are they elsewhere in the room and the mirror at the back reflects them at an angle? Or is that a painting of them and not a mirror at all?

source: Computer graphics synthesis for inferring artist studio practice: An application to Diego Vel'azquez's Las Meninas - David G. Storka and Yasuo Furuichib - aRicoh Innovations, 2882 Sand Hill Road Suite 115, Menlo Park CA 94025 USA and Department of Statistics, Stanford University, Stanford CA 94305 USA bKanagawa, Japan

Las Meninas, though made in a traditional style and medium, was so revolutionary and fascinating in theory that, centuries later, the founder of Cubism and artistic Modernism, Pablo Picasso, created 44 studies of it in his own style. 44 perspectives exploring the complexities of perspective and realism. Like 44 lovingly broken shards of the mirror that is Las Meninas.

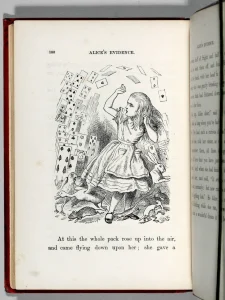

It may seem that we've tumbled through the looking glass, as mirrors used to be called. That's an intention reference to the sequel to Lewis Carrol's Alice in Wonderland. Passing through the looking glass, tumbling down the rabbit's hole, stepping through the back of the wardrobe into Narnia-all of these are literary portals into alternative worlds, which function under their own rules. Before the conceptualization of computers, programming and the creation of digital worlds, artists and writers conceived of alternative worlds accessed via the imagination, with paintings and texts serving as aids to stimulate the immersive experience of the audience. That audience must meet the creator halfway, offering themselves up by willingly suspending their disbelief.

Matteo Moriconi

_______________________________________

President of the Brazilian Association

of Visual Technology

in collaboration with Dr Noah Charney, Professor of Art History